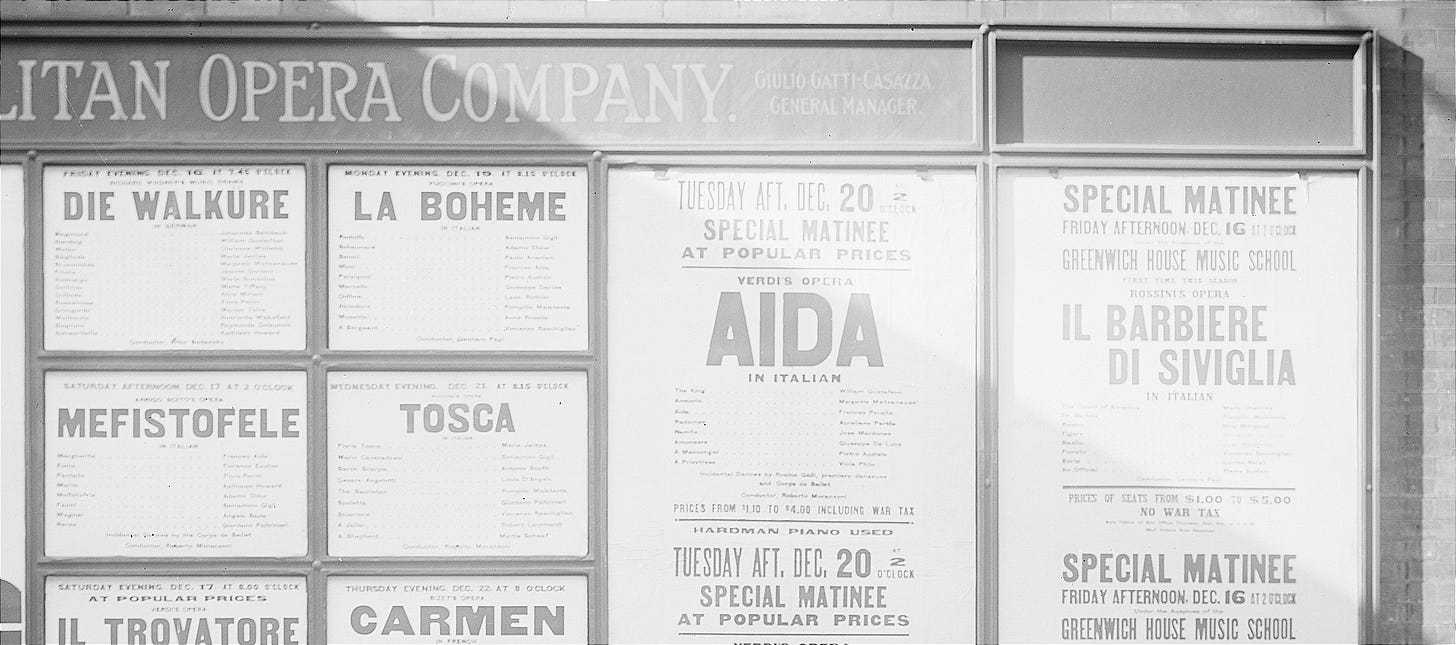

Going to the Opera in New York City

Reflections from the Metropolitan Opera House, and a guide for the opera first-timer

I feel fortunate that I grew up in a family that cared about the arts, trying often and as best they could to expose my brother and me to museums, concerts, theater, and the like, even as young children. The exposure has paid dividends throughout our lives and is no doubt why I unflinchingly include opera in my monthly Blankman List.

My dad especially was into classical music, always encouraging me to listen to and play it. I’ve had (and actually asked for!) lessons in piano and other instruments since I was in elementary school, and my bulky 88-key weighted keyboard has followed me to even my most cramped dorms and living quarters. NYC shoebox apartments be damned; an instrument that plays and feels like an actual piano has been nonnegotiable wherever I’ve lived. Several years back, I remember hearing a coworker explain to me how classical piano repertoire mustn’t be played on a digital piano. ThAt’s NoT whAt It’S sUPpoSed to SoUnD liKe. I felt myself straining to stay civil.

One place where a background in classical music benefits me is at the opera. I sometimes forget that the opera is not where most bored New Yorkers pass their Sunday afternoons. I freely bring it in up in small talk like, “do anything interesting over the weekend?” or “what have you been listening to lately?” I’ve gotten surprise and incredulity.

Listing Operas I’ve Seen

Since I love list-making so much, I tried to document what I’ve seen. As far as I can remember and as of this writing, I have seen only (or a whopping, depending on your perspective) 18 distinct fully-staged operas:

Aida (multiple times)

Ainadamar

L’Amour de Loin

The Bartered Bride

La Bohème

Dead Man Walking

Dialogues des Carmélites

Fire Shut Up in My Bones

Florencia en el Amazonas

Grounded (twice)

The Hours

Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk

Madama Butterfly

Maria Stuarda

Rigoletto (multiple times)

Tosca

Werther

Written on Skin

I’ve also seen cabaret performances of L’Elisir d’Amore and Falstaff, film screenings of La Traviata and Falstaff, and a concert performance of Emmett Till (which, to my knowledge, has never been staged). Lord only knows how many scores I’ve listened to. I am quickly humbled by the comparable list of many an opera buff. But I am also aware that’s approximately 18 more operas than many of my friends have seen.

In this post, I reflect on my years attending different operas. I also try to break down for the uninitiated a quick guide to the opera, most specifically as it relates to seeing one at NYC’s Metropolitan Opera House. I’m aware that opera is not always the most accessible of art forms, and there is nothing wrong with having never seen it or not feeling interested in it. But if you’re a little bit curious or perhaps a little bit daunted, then I wrote this post with you in mind.

What Is Opera?

Let’s start with the basics, although I’m frankly not so sure how “basic” this question is. There’s at least a stereotype to start from: singers belting at the extremes of their vocal ranges, epic stories of love and death, classical music played by huge orchestras. If you ever catch a performance of Turandot, you will be treated to this sweeping number, sung here by SeokJong Baek during a Met Opera dress rehearsal earlier this year:

Truth be told, it is the classics of the canon—Madama Butterfly, Turandot, Carmen, and the like—that keep most opera houses alive, and they more or less match the stereotype. But opera is a rich art form and defies expectations all the time. A few memories along those lines:

Dead Man Walking begins with a video of sexual assault and murder and (spoiler alert!) ends with a video close-up of death by lethal injection.

One scene of Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk “culminates in the most graphic depiction of orgasm in the operatic canon, complete with gliding trombones” (note: article behind paywall).

I swear that the most common word, or at least interjection, of Grounded is “fuck.” (OH, my stars!)

There was even an opera staged in Stuttgart, Germany a few months back that made headlines for being in such questionable taste that 18 audience members required medical treatment for nausea after the performance. Suffice to say, that’s unlikely to make the Blankman List (or, realistically, even transfer to another opera house). On a less shocking note, plenty of operas have speaking and dancing in them, and the music definitely does not always sound like that of the belting cartoon diva.

I want to roll my eyes even writing this out, as it makes my post read like a freaking dictionary, but it’s hard to discuss opera without using a few terms that someone who’s never before engaged with the art form may not be familiar with.

Aria and recitative: In most operas, the singers never stop singing. However, the singing can be divided into two broad forms: an aria is a traditional song with verses, choruses, themes, development, and the like, whereas recitative (most commonly pronounced “RESS-uh-tuh-TEEV”) is dialogue that is set to music.

Score and libretto: The “text” of an opera includes both the musical score (which is documented as sheet music) and the libretto, which is the written script of the words being sung. The composer writes the score, and the librettist writes the libretto.

Opera vs. Musical Theater

The closest comparison that many of my friends have seen is musical theater. That too is drama with singing, and sometimes with equally elaborate sets and costumes, not to mention plenty of racy productions. In fact, it’s not always black and white what counts as what. To scratch the surface, Sweeney Todd, West Side Story, Porgy and Bess, Oklahoma!, and Carousel have all been staged as both opera and musical theater. I’ve heard pop music in opera scores and classical music in theater scores.

Both opera and musical theater, however one thinks of them, are major collaborative art forms that at their most resplendent require hundreds of people to mount: stage designers, musicians, producers, ushers, marketers, and so on. “As an amalgam of virtually all the performing and visual arts,” writes Peter Gelb, the general manager of the Metropolitan Opera, “opera has the singular power to reveal the essence of our humanity.”

Here, I venture into personal point of view, but in my mind, the biggest difference between musical theater and opera is that in opera, music comes first. I don’t necessarily mean literally. Plenty of operas have been written after or alongside the libretto or been tweaked once on stage. But fundamentally, at least to me, an opera is about the music. It comes before lyrics, which aren’t easily understood anyway. It comes before the direction, which must work with the score, not dictate it. It comes with expectations that opera singers can handle extremely difficult vocal writing and are not “actors first” or “dancers first.”

And it comes with prestige. The composer of an opera is usually how the work is known to the world. Opera novices probably know that Giacomo Puccini composed Madama Butterfly (though they may not know his first name, Giacomo). Even opera buffs, however, would be forgiven for not knowing that the opera’s librettists were Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa. So if you imagine a spectrum that goes from “drama with music” to “music with drama,” musical theater is usually in the middle, and in some song-light shows like 1776 or the film version of Dear Evan Hansen (shudder . . .), the music almost seems secondary.

Opera, on the other hand, is firmly on the “music with drama” side of the spectrum. In fact, opera is sometimes performed as a straightforward concert with no story acted out. Most opera is sung through, i.e., instead of spoken dialogue in between songs, there is continuous music in the form of recitative and arias. Some musicals do this, too, incidentally. Rent, which is sung through with pop music recitative, is famously based off of the opera La Bohème.

Another oft-cited difference is opera singers don’t need microphones. It is the craft of singing being practiced at the most technical extreme. There are physical costs that come with that—something I imagine athletes and sports fans can relate to. Any given opera does not run eight times per week like a Broadway show or even four to five times per week like a baseball game; the singing is too demanding. Also, you will not see opera singers being asked to dance or sometimes even act like a Broadway performer. Some can! And plenty of performers have worked on both opera and Broadway stages. But an opera singer is hired for voice above all, and Broadway-style choreography is more or less impossible while singing opera.

Preparing for the Opera

A difference between operas and musicals that many people find off-putting is that in opera, the words are hard to understand. In fact, the words are often not even in English. Regardless of the language, the words are typically displayed as captions. A common setup in many opera houses is to display the libretto as surtitles projected above the stage. When I saw L’Elisir d’Amore, the words were shown on a makeshift screen propped up on the stage’s floor. The Metropolitan Opera House does something mesmerizing the first time you see it: the captions are in front of every seat. They’re displayed on soft red LED screens that you can toggle on and off and choose among different language options.

Shifting your attention between the action on stage and the screen in front of you can get annoying, but in most operas, you’ll discover it’s not that crucial to read every word anyway. It might take the diva like three damn minutes to finish singing, “I’m dying.” Before seeing an opera, it’s common to not worry about spoilers and read the plot. In fact, it’s typically written right in the program so you can prepare yourself before the opera starts. The story may be a driving factor behind a staggeringly large work of art, but it is ultimately secondary to the music.

Personally, I also like to listen to the music (if possible!) in advance of going. People are divided in this regard, but I swear if you play an aria enough times, the song will start to get stuck in your head. One of the reasons I love seeing Rigoletto is that I’ve listened to the score so many times that it feels like seeing a band I love in concert. “Oh hell yeah, they’re playing my song!”

Getting to the Opera

Part of me writing all this down was with the opera newcomer in mind. There’s no question that opera still has a few trappings of upper class Victorian Era Europe. It’s viewed as something fancy, a special occasion. For me, that’s kind of a shame. It doesn’t need to be a special occasion to experience great music!

The most common question I see online from people attending the opera for the first time has nothing to do with surtitles or librettists or musical themes; it has to do with how to dress. It’s a reasonable question. In TV and movies, opera attendees arrive in limos and are dressed to the nines. In reality . . . not so much, at least at the Metropolitan Opera House, the place where I turn my attention for the rest of this post.

Plenty of people do make a special night (or day) out of it, but plenty also just really love opera and are coming perhaps from work or from an exhausting day of walking and sightseeing. I’ve seen people in shorts and a T-shirt, and nobody bats an eye. The Met does not have a dress code. On average, people are dressed nicely, but not excessively so.

I like to arrive around 30 minutes ahead of time, which is enough time to peruse the gift shop or explore the cavernous venue before the show. I can’t remember if I’ve ever even bought from the gift shop. It doesn’t matter. There’s something unique about riffling through aprons with music puns and Blu-rays of ballets.

Attending the Opera

I always order my tickets for will-call. It’s a little less eco-friendly, but so help me—I like the actual ticket stub. I often have a full-size backpack with me, sometimes even with snacks and a laptop, and it has never been an issue. I rarely use it, but there is a coat check in the lower level for $5 per item.

There are a ton of bathrooms, most with lush waiting areas. There are water stations with hands-free but frustrating faucets, and dotting the expansive opera house are paintings, decorative art, and small exhibitions. I frankly feel a little awkward trying to admire a painting with my free water and huge backpack in the presence of such urbanity, but it’s hard to look away from Shara Hughes’ stunning commission.

Truth be told, when I saw Ainadamar earlier this year, one of my favorite features was that it was a single act. The airy, abstract opera that counted Spanish flamenco and Cuban mamba among its influences was breathtaking for around 80 minutes and then finalizada. That’s the exception, though. Usually, there’s an intermission long enough to literally grab a quick (and obscenely priced) bite at the Grand Tier Restaurant inside the building. For some of the really long classic nineteenth-century operas, like La Traviata and Tosca, there are two intermissions.

Watching the Opera

It feels like an unspoken question. What do I do while I’m watching it? Let me be perfectly transparent: despite my love of the art form, I feel bored sometimes. I feel antsy sometimes. I have wished I were home. My mind wanders, and I am thinking about seemingly anything but the opera. “Hmm, I feel cold but don’t want to disrupt everyone by putting my jacket on.” “Shoot, did I leave the air conditioner on at home?” “I kind of want to get ice cream afterwards.”

I rein myself in and try to stay present. For me, it is always the music that makes it possible. I like it when I catch the moment the music goes from recitative to aria, although usually I miss it. Often I am drawn to the orchestra. The Met Opera’s orchestra pit can accommodate over 100 musicians—over four times that of even the largest Broadway theaters. Some of my favorite operatic moments are in fact orchestral ones. I remember being transfixed by the harp lines in Werther or the pianist plucking the piano strings like a guitar in Grounded. I am in constant awe of how no matter where I’m seated, the orchestra’s timing is blisteringly perfect. Sometimes, it’s not the music, too. The step dance in Fire Shut Up in My Bones, which continues long after the clip below, is electrifying:

The sets can be daring and the costumes extravagant. The Met isn’t known for sparing expenses. Shows have included experimental lighting design and dozens of dancers and chorus members (see above); Aida has an entire parade—with live horses! There is no wrong way to find your way in. Give yourself grace if you struggle to stay focused, and let yourself be captivated by whatever gets your focus back.

Reflecting on the Opera

In my view, it’s perfectly fine to leave an opera, not quite sure of what you just saw. Part of it seems so archaic. We’ve invented the microphone, for goodness sake! Do they really need to sing like that?

But this isn’t just singing, it’s singing, taken to the logical extreme. Artisans who are the literal best in the world at their craft. I’m unbothered by music that is tough to grok at first listen. For me, music is nourishment. Time filled with sound, provocation, inspiration. Perhaps it’s a bit like reading a book. Even when the plot lines and histories have long escaped my memory, my time reading it was nourishment just the same. For opera is Art with a capital A.

There’s no denying that opera is an outmoded art form, and listening attentively for hours on end is not always easy. I do it because I know this: when I give an opera my attention, it gives back. I leave with a perspective that’s just a little bit different. An experience that’s just a little bit formative. And the best part for me: my musical horizons just a little bit broadened.